THE INDIAN SUB CONTEXT – NPC-AMASR AND CORRELATING THE BURRA AND INTACH CHARTERS

25. In the Indian context, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)’s National Policy for Conservation of Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (NPC-AMASR) attempts to incorporate the “Values Based Approach” in Section 5 titled “Conservation of Monuments” and functionally link the nature and extent of intervention required to the value/significance of the monument to be conserved and its “typology”. Clause 5.02 of the document says, “Preservation should be the major objective in the case of monuments with high archaeological value”. While Clause 5.03 elaborates that in the case of monuments with “high architectural value”, restoration work may be undertaken only “in parts of a monument wherein there are missing geometric or floral patterns” and “at no cost shall an attempt to restore an entire building be allowed as it will falsify history and will compromise its authenticity. Similarly, decorative features such as wall paintings, inscriptions, calligraphy and sculptures should also not be restored.” Clause 5.04 restricts “Reconstruction” to “extreme cases” where such an intervention is “the only way” to “retain or retrieve their integrity/context” and to be undertaken “only on the basis of evidence and not conjecture”. Clause 5.05 says, “Reproduction of members of a monument may be undertaken’ only after a thorough debate and for such a monument ‘whose original members (structural and/ or ornamental) have deteriorated and lost their structural and material integrity and removing these…is the only way to safeguard those members as well as the monument itself.” It also stipulates that if the reproduced members are to be reinstated to ‘their original location so as to maintain authenticity, their form and design should match the replaced “deteriorated” member and they should be distinguishable from the original members (National Policy for Conservation of Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains 2014).

26. In India, however, there is no conservation charter at the national level to delineate and codify guidelines for conservation of heritage. The INTACH Charter of 2004 has attempted to amplify some aspects of the Burra Charter, and contextualize it. For example, Article 3.2.2 of the INTACH Charter states: “An exact replacement, restoration or rebuilding must be valued when it ensures continuity of traditional building practices” (INTACH Charter 2004, P. 8). Here, not only an added emphasis on the importance of traditional building techniques and skills is evident but also an aspiration to restore the monument to its original aesthetics.

27. While the Burra Charter states that the cultural significance of a place can change, Article 3.3.2 of the INTACH Charter propounds “the concept of an evolving integrity” that accepts the introduction of new materials and techniques when local traditions are insufficient. For example, during restoration work of Humayun’s tomb, help from craftsmen from Central Asia was taken for the tile work on the cupolas as the required techniques were not available locally.

28. The Burra Charter, as indicated earlier, encourages people’s participation in conservation. The INTACH Charter does the same with greater emphasis. Article 3.5.1 of the INTACH Charter seeks to: “encourage active community participation in the process of decision-making. This will ensure that the symbiotic relation between the indigenous community and its own heritage is strengthened through conservation” (INTACH Charter, P. 8). In the case of Humayun’s Tomb, even though the community participation at the decision-making was limited, the community was actively involved in the restoration work and a number of traditional skill-development and welfare projects were launched in the area (Nizamuddin) under the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative by AKTC strengthening this “symbiotic” relationship.

29. The updated Burra Charter highlights the importance of traditional building skills. However, the emphasis on traditional building skills is probably even more marked in the INTACH Charter. Its Article 3.9.1 states: “The nature and degree of intervention for repairing, restoring, rebuilding… should be determined on the basis of the intervention’s contribution to the continuity of cultural practices, including traditional building skills and knowledge” (INTACH Charter P. 9). Given the strong handicrafts tradition in India, the INTACH Charter understandably also lays more emphasis on “living heritage” (the concept of living heritage is elaborated at para-41 below).

30. The Burra Charter is cautious about additions and alterations, whereas Article 3.8.2 of the INTACH Charter says “substantial additions and alterations may be acceptable provided the significance of the heritage is retained or enhanced” (INTACH Charter P. 9). However, the difference is more of degree and the INTACH Charter comes across as more open in its approach in this regard. As indicated above, substantial alterations such as re-laying of lower and upper plinths were carried out to restore the authenticity and visual appeal of the structure and even probably enhance it. This work was in keeping with the principles underlying INTACH Charter’s above-mentioned Article as also the Burra Charter.

31. The Burra Charter has been a major advancement in terms of expanding the scope and definition of a “place” or site that should be conserved. The INTACH Charter elaborates on this, especially in the context of historical urban settings. For example, its Article 6.2.1 states: “In general, Heritage Zones are sensitive development areas which are a part of larger urban conglomeration possessing significant evidence of heritage” (INTACH Charter P. 17). In the case of Humayun’s tomb, which is a world heritage site, AKTC has proposed to develop the entire Nizamuddin area, particularly the poorer quarters, as also a number of unprotected smaller structures existing in the area.

Images above show the change along the Barapullah Nullah as part of efforts to develop the public spaces in the Heritage Zone in Nizamuddin area.

32. Lastly, the Burra Charter does not favour restoration or rebuilding based on conjecture while the INTACH Charter allows restoration and rebuilding based on conjecture as long as this practice is based on traditional knowledge systems – myths, folklores, beliefs and rituals.

CRITIQUE OF THE BURRA CHARTER

33. There exists a view that deeper consideration towards the philosophical framework for evaluating cultural significance is required. The Burra Charter states (Article 1.2) that ‘cultural significance is embodied in the place itself’. However, significance cannot be possessed by the place; instead, values and significances are projected by humans onto concepts, memories and substrates. Thus, identifying values becomes tied to the “meanings” individuals and social groups attribute to objects over time. However, this criticism is not entirely justified as Article 1.2 also goes on to say that “Places may have a range of values for different individuals or groups” (Burra Charter P. 2) thereby confirming that aesthetic is politically and socially contingent.

34. In their article “Judgment and Validation in the Burra Charter Process: Introducing Feedback in Assessing the Cultural Significance of Heritage Sites”, Silvio Mendes Zancheti, Lucia Tone Ferreira Hidaka, Cecilia Ribeiro & Barbara Aguiar propose to redefine cultural significance as the set of all identifiable values resulting from continuous (past and present) judgment and the social validation of meanings of objects. This implies that significance includes past and present values, those that are in dispute among the stakeholders, and those with no more meaning in the present, but that are still in the collective memory. Such an amendment in definition would imply that the value included in the statement of significance, based on identification of meanings, would need to be validated among stakeholders. If not validated, the significance needs to be reassessed thus building a system of feedback in the Burra Charter Process.

35. There is also a view that the Charter could further expand on the thinking behind the important Explanatory Note at Article 5.1, ‘In some cultures, natural and cultural values are indivisible’ (Burra Charter Page 4). The difficulty in assessing relative cultural significance (Article 15) and the simultaneous avoidance of unwarranted emphasis on any one value at the expense of others (Article 5) can also lead to conflicting situations (Argyro 2016, pp 108-9).

36. In the Indian context, especially in a densely populated urban area, the alienation of people of the area that is proposed to be conserved poses immense challenges such as in the case of the old city of Shahajanabad in Delhi. This probably makes it imperative to have an interim arrangement/mechanism for sustained discussion between various stakeholders to enable progress towards a joint statement of significance of the place so that appropriate policy, based on consensus or as close to consensus as feasible, can be framed. The Charter could also consider to elaborate on, under Article 34 on resources (Burra Charter, p. 9), the synergy between heritage and tourism and adaptive or creative reuse, especially in the context of developing countries that face a resource crunch. Such a step could also add another dimension (economic) to the Charter.

OTHER VIEWS ON VALUES-BASE APPROACH AND CRITIQUE

37. Going back to the wider deliberations on the values-based approach, it needs to be mentioned that the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) has also produced a series of research reports seeking to define the values-based approach. In one such report, the basic elements of the values-based approach are outlined emphasizing that it has the purpose of “protecting the values of a cultural entity, be it place, or object as decided, as per designated criteria, by government authorities or other owners and other citizens with legitimate interests in the place or object. These reports promote the necessity of multiple stakeholders in conservation decision-making, but acknowledge a lack of cohesive methodology for assessing values (de la Torre, MacLean, Mason, Myers 2005, p. 5).

38. In response to issues related to methodology pointed out above, authors such as Barbara Applebaum have attempted to come up with decision-making guidelines under this approach. She uses information gathered from relevant stakeholders to characterize and reconstruct the history of an object to determine the ideal state of preservation. She also lays out a process of categorizing key values such as art, aesthetic, historical, use, research, educational, age, newness, sentimental, monetary, associative, commemorative, and rarity (Applebaum 2007). Separately, in a document deliberating on the values-based approach, the Government of Australia states, “integrating contextual knowledge and stakeholder input” is the “central core” of decision-making.

39. Conservation professionals are in some ways still coping with the paradigm shift from a materials-based approach to a values-based one and study of the values-based approach is ongoing. Over time, it is expected to evolve further. The approach or its practice, however, has also come in for criticism. Commenting on the future of conservation in an interview, noted theorist Elizabeth Pye underscored the movement towards “social conservation” which envisions a wider dissemination of conservation knowledge and skills, within the field, to allied cultural heritage professionals, and the public alike. Pye believes that knowledge dissemination is a tool to promote the relevance of heritage conservation in society (Pye 2011).

40. Marta de la Torre and Randall Mason of the GCI have pointed out the inherent issues of the values-based approach that conservators must tackle – “conservation professionals are faced with two particular challenges arising out of the social and political contexts: challenges of power sharing and challenges of collaboration.” There is a growing demand in the conservation world for “shedding insular attitudes” and accepting “multiple voices” in workplace dynamics and decision-making. Additionally, the values can be conflicting. For example, the use value which in the conservation of monuments and buildings can lead to renovations to ensure solidity and continued use of a site may conflict with the age value as incomplete or ruined monuments and sites may be dangerous to the public and therefore inaccessible. In the case of conflict between differing stakeholders and between alternative values, a values-based approach does not provide sufficient criteria and ways to set priorities between them and indicate which ones to favour. It encourages community involvement but does not seem to set the terms for this involvement. Another weakness of the approach is linked to the power of one lead managing authority in the planning and implementation process (de la Torre, Mason 2002 pp. 3-4).

41. Moreover, there is a view that a specific category of sites called ‘living heritage sites’ cannot be embraced within this approach. The key concept in the definition of a living heritage site is that of continuity comprising: (a) functional continuity; (b) continuity of the process of maintenance and arrangement of the social as well as physical space of a site; and (c) continuity of the physical presence of a site’s community in a site. Another key concept in the definition of a living heritage site is that of change, in the context of continuity. Changes in the function, the space, and the community’s presence, in response to the changing circumstances in society at local, national, and international level, are seen as an inseparable element of continuity and an essential requirement for the survival and continuation of a living heritage site. These concepts of continuity, change, and core community are illustrated in: The Temple of the Tooth Relic in Kandy in Sri Lanka and the monastic site of Meteora in Greece, both World Heritage Sites (Poulios 2010).

42. The values-based approach is likely to change and adapt as efforts continue to closely align the theoretical basis for conservation-work to current practice. This ongoing process can be expected to lead to enhanced sharing of conservation knowledge a key element of Pye’s social conservation model and a broader understanding of authenticity so as to encompass widely varying contexts that prevail across the world.

THE STRUCTURE OF COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION IN CONSERVATION

43. The relevance of community participation in conservation and development of basic facilities in the heritage zone as recommended in the Burra and INTACH charters and highlighted above in the case of the restoration of Humayun’s tomb has become increasingly evident. However, a key question for cultural heritage practitioners remains: how to encourage participation by the community in the complicated processes related to the conservation of cultural heritage? The concept of ‘community’ itself is complex. One of the earliest definitions of community was offered by the German theorist Ferdinand Tonnies through his distinction between ‘Community’ and ‘Society’. Tonnies argued that traditional forms of living were characterized by the formation of communities. Whereas modern industrial societies need to be understood as more structured and defined by their formal institutions. Since this original definition, many others have tried to explain in more detail what ‘community’ means. Generally, it is agreed that communities occur when people get together and form groups out of both self-interest and the interest of the wider group. It is often said that people ‘belong’ to a community, i.e. they feel loyal to the group, and share in its goals, values and beliefs. A monastic order is one example of a strong community, whereby monks collectively abide by and follow a clear set of beliefs, rituals, rules and values (Tonnies 2002).

44. Recent research has also revealed how communities can take on very different forms in modern life. The internet, for example, has created a whole new generation of ‘online communities’, where people from very different parts of the world meet on the World Wide Web because of shared interests. This globalization of communities can be seen across the world for example in the fan communities associated with world football. Supporting a particular team not only makes people part of a global community of football fans, but also gives them a sense of identity that is in relation to others around them, including supporters of opposing teams. Hence, communities do not necessarily need to be as geographically specific as neighbourhoods, and communities are formed more around shared interests and the desire to have a sense of identity that can only be achieved by being part of a larger group.

45. In the context of cities, the British planning theorist Nick Wates also defined community in terms of shared interests, but added that communities are particularly strong when these groups live within the same geographic area. We can thus see that in many cases there are clear overlaps between ‘community’ and ‘neighbourhood’, both in terms of definition and their geographic location. It is important to remember though that there might be a number of distinct communities within a particular neighbourhood, and that any particular community might cut across several neighbourhoods. Given that communities are said to have a shared set of values, beliefs and interests, it is often possible to identify a ‘spokesperson’ for that community, or someone who can represent the community – ‘the community leader’, or in rural settings ‘the village chief’.

46. Heritage is definitely more than the sum of recognized objects worthy of being protected; it has to be approached as a territorial system where the relationship between the physical heritage and human actions is an integral whole. The Council of Europe “Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society”, signed in 2005 in Faro (Portugal), can be considered as a turning point as far as defining and formalising the role of communities in the protection of cultural heritage goes. It aims, firstly, at emphasizing the value and potential of cultural heritage to be wisely used as a resource for sustainable development and quality of life in a permanently evolving society, and secondly at reinforcing social cohesion by fostering a sense of shared responsibility towards the places in which people live. The concept of heritage community was officially defined, possibly for the first time, as a group that values specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish to protect and transmit to future generations, and which reflects the need to open public participation in discussions related to cultural heritage (Cimadomo 2012, p. 94-95).

47. Planning for community participation has been broadly classified under two approaches: problem-oriented planning and asset-based community development (ABCD). Two examples/issues generally related to problem-oriented planning involve land use and environmental pollution. Generally, problem-oriented plans are dictated by a short time frame with a deadline, surrounded by a sense of urgency, and driven by resource demands and priorities. The problem-oriented planning process includes the following steps: define the problem; articulate goals and objectives; analyze and evaluate; implement action plans; and measure results. The problem-oriented planning process can be seen throughout the developing world, where city and regional planning authorities are often reacting to problems arising from population increases, economic development, political shifts, and environmental changes among other factors.

48. In contrast, asset-based community development (ABCD) seeks to uncover and highlight the strengths that already exist within communities. The basic idea is that a capacities-focused approach, which emphasizes the positive capacities within communities, is more likely to empower those communities and, therefore, mobilize citizens to create positive and meaningful change from within. Instead of focusing on a community’s needs, deficiencies and problems, the ABCD approach helps them become stronger and more self-reliant by discovering, mapping and mobilizing all their local assets. These assets include: the skills of citizens; the dedication of citizens’ associations (temples, clubs, and neighbourhood associations); the resources of formal institutions (businesses, schools, libraries, hospitals, parks, social service agencies). For those engaged in asset-based community development, actions include: collecting stories of community successes and analyzing the reasons for success; forming a core steering group; building relationships among local assets for mutually beneficial problem solving within the community; convening a representative planning group; leveraging activities, resources, and investments from outside the community; and mapping community assets.

49. Community Asset Mapping is the inventorying of the assets of individuals and organizations. It is increasingly being used by cultural heritage practitioners as a means of understanding the positive elements that exist in a community, so that more sustainable solutions can be implemented for protecting valuable cultural resources. The community assets approach starts with what is present in the community, concentrates on agenda-building and problem-solving capacity of the residents and stresses local determination, investment, creativity, and control. Some forms of mapping include: Mapping Public Capital (social gathering places) – identifies the places where people congregate to learn about what is happening in a community; Mapping Community Relationships delineates the relationships between organizations within a community; and Mapping Cultural Resources that documents cultural resources in a community (Sapu 2009). As illustrated below (para: 55-58) in the case study discussing the renovation of Humayun’s tomb, this approach has been widely used, whether by identifying and creatively utilizing places of social gatherings for cultural performances or by identifying and utilizing the crafts known to the community such as Sanji (traditional craft of paperwork).

50. There are three main approaches to asset mapping: (i) the Whole Assets Approach; (ii) the Storytelling Approach; and (iii) the Heritage Approach. The ‘Whole Assets Approach’ takes into account all the assets that are part of the people’s view of their immediate community as well as the surrounding world. The ‘Storytelling Approach’ produces pieces of social history that reveals assets in the community. It identifies how assets that are often hidden or dormant can be put together with other assets to produce additional assets. The ‘Heritage Approach’ produces a picture (map or list) of those physical features, natural or built, that make the community a special place. Assets include natural heritage features such as rivers or beach as well as built features such as an old bridge or a historic building (Sapu 2009).

51. It is seen that community participation in conservation has, on the one hand, benefited from the downturn in real estate development, especially in those countries where conservation is relatively weak compared to the power of the property developers. On the other hand, in a number of countries it has suffered from cuts in government spending and the consequent decrease in finances available to organizations involved in heritage conservation. Such a decrease in the funding of heritage conservation and preservation projects, both big and small, have had, in some cases led to irreversible damage or even disappearance. These economic and social changes, together with new information technologies and social media networks, have provided new opportunities to share concerns and have increased social conscience and facilitated citizen participation in, and funding possibilities of, many kinds of socially-orientated urban projects. Such participatory practices have encouraged the recovery of public spaces, which in turn has served to strengthen the cultural identity of the inhabitants of the surrounding neighbourhoods. Through the use of communication networks, local urban transformation projects can be ‘delocalized’, making possible a global resonance unimaginable a few years ago.

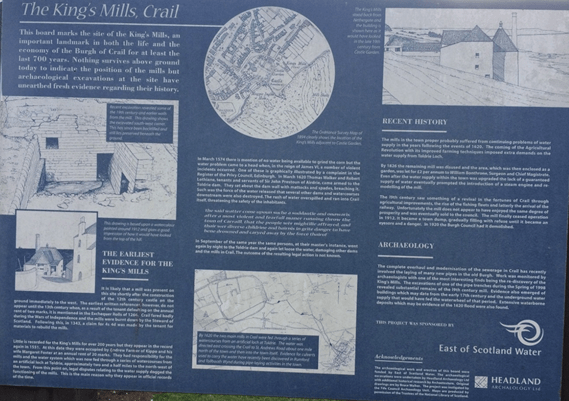

52. A number of case studies such as conservation work along Scotland’s coastline show how it is possible to create new models of urban transformation that respond to the needs of citizens, and encourage the social responsibility required in new models of production in our society. They reflect a new way of planning, where co-participation and new ways of application and management of public values is possible (two photographs – Images-8 & 9 of the Eastern Scottish coast at Crail are illustrative). Information technologies offer new opportunities, and not only show new ways to engage communities in safeguarding cultural heritage at risk, but also how innovative, original methods of heritage protection can be developed when citizens are given more decisional power. The Periodic Report and Regional Programme for Arab States (UNESCO 2004:40) recognizes how one of the most important things determining the preservation level of cultural heritage, is local human activities.

53. For this reason, stakeholder participation in all phases, from identification to registration to management, should always consider the implementation of participative processes and foster a sense of shared responsibility towards the places in which people live. Technologies have improved citizen networks, their mobility and activities including the claim for cultural identity as the only thing that differentiates one people from the other in a globalised world.

54. When it comes to developing countries like India, the relevance and importance of community participation acquires a more urgent resonance as issues of conservation get linked to issues of development such as providing basic infrastructure and livelihood opportunities to communities residing in the vicinity of cultural sites. Simultaneously, however, effective community participation also becomes much more complex because of the heterogeneity of population and their differing views that get reflected in different stakeholders pulling in different directions. Also, in many cases, the composition of the community residing in an area has changed significantly over time. In many cases, these may even be encroachers. However, they might need to be consulted all the same and taken on board, especially if they have been living there for long. The quick pace of modern economic growth and its pulls and political contextualization also have a bearing that needs to be kept in mind. In more complex and contentious cases, first building a minimum level of trust between stakeholders and encouraging a broad consensus toward a common vision may be critical, to reply to the key question posed earlier: how to encourage participation by the community in such cases? Simultaneously, incentivization may be required to progress toward a common vision, which itself might require adjustments from all sides and prompt action against any activity that adversely impacts the heritage may be required. All these are easier said than done in complex situations such as in the case of Shahjahanabad where alignments are deeply problematic. So, perseverance by the conservation community becomes essential in bringing together the stakeholders.

BRIEF CASE STUDY – RESTORATION OF HUMAYUN’S TOMB

55. As underlined above (para 17-22) during the course of the discussion on the Burra Charter, the restoration of Humayun’s Tomb is a recent, illustrative case of application of the values-based approach in a systematic manner. The main stakeholders (the ASI and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture – AKTC) worked in close partnership with public (Municipal Corporation of Delhi, Central Public Works Department & Delhi Development Authority) and private partners such as the TITAN Company and the local community to restore the architectural integrity of the mausoleum and all attached structures including the gateways, pavilions and enclosure walls. After exhaustive archival research, site surveys, documentation using three-dimensional laser scanning technology, condition assessment and structural analysis, detailed conservation proposals were prepared and the conservation works commenced in April 2008.

56. During conservation work, authenticity of design, form and material was maintained. For example, over a million kilos of 20th century cement was removed from the roof terrace and large-scale paving of the lower plinth using the original Delhi Quartzite undertaken again after removing huge amounts of concrete. Similarly, restoration of glazed tile-work on the canopies (on the roof) was undertaken only after the original patterns could be determined and after imparting training to local youth of the area by master craftsmen from Uzbekistan. All existing tiles were retained (age and historical value) even though they had lost their glaze. The conservation project is also illustrative of an attempt to encourage community participation and development as it also encompasses the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative that aims to develop the area into a historic and cultural centre of Delhi (Exhibition on Conservation Work at Humayun’s Tomb, 2016; The Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, p. 169).

57. Conservation works in the densely populated Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti started following the partial collapse of the 14th century Baoli (step-well), still fed by underground springs, in July 2008. The Baoli was desilted to its original levels and the collapsed portions rebuilt. The enclosures of a unique Mughal tomb known as Chaunsath Khamba and the tomb of Mirza Ghalib were landscaped to enhance the historic character of the area, while also creating performance spaces for musical traditions associated with the area over centuries. A number of socio-economic initiatives aimed at improving the quality of life of the local residents and pilgrims were also undertaken through a collaborative approach. These interventions were in the areas of: education, health, sanitation and upgrading open space. For example, parks along the western edge of the Basti were landscaped to suit the needs expressed by the resident community in consultative meetings and hundreds of household toilets were connected to the sewerage system and portions of the sewerage system re-laid (The Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, p. 170-71). A set of illustrative photographs related to the community participation initiative in Nizamuddin area are attached separately as appendix.

58. Despite marked improvements in a number of socio-economic indicators such as increase in school enrolment, sanitation and creation of open spaces, the pressure of the resident population and the growing number of pilgrims on public resources/utilities has led to difficulties in upkeep and maintaining cleanliness in the area including keeping the Baoli clean and free of plastic waste. Also, many stories around a number of significant monuments such as Jahan Ara’s tomb, who was a Murid of Nizamuddin Auliya and whose tomb lies near Hazrat Nizamuddin’s tomb, are waiting to be told.

BRIEF CASE STUDY – MEHRAULI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK (MAP)

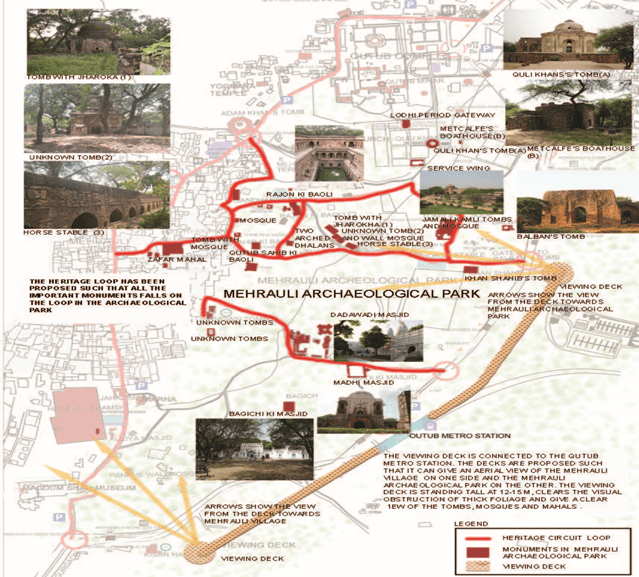

59. The Mehrauli Archaeological Park contains hundreds of historical monuments and ruins of cultural significance including the pre-Islamic walls of Lal Kot dating back to the 11th century; the remains of the city of Qila Rai Pithora built by Prithviraj Chauhan in the 12th century; the tomb of Ghiyas-ud-din Balban (built in the 13th century); the Jamali Kamali mosque (adjoining the tomb of Sufi Pir Jamali); Rajaon-ki-Baoli dating back to 1506; the tomb of Quli Khan, one of the commanders of Akbar, which was later modified and added to by Metcalfe, the British Agent (negotiator) at the court of Bahadur Shah Zafar; and Jahaz Mahal built during the Mughal period to name a prominent few. These monuments are located in a natural habitat that is a mix of landscaped and wild/semi-wild areas. SDMC has named 127 monuments in the park as heritage monuments of which six structures are centrally protected by the ASI and 17 declared as heritage monuments of state importance by the State Archaeological Department (SAD).

60. In contrast to the remarkable renovation work and useful social engagement carried out at Humayun’s tomb, Sunder nursery and Nizamuddin Basti, the efforts at restoring the significance of the Mehrauli Archaeological Park continue to flounder despite a 2015 PIL filed by INTACH in the Supreme Court, which led to the formation of a SC-appointed Monitoring Committee. There has been some progress in the last few years leading to an increase in footfalls but a lot more needs to be done.

61. Key issues connected with the Mehrauli Archaeological Park (MAP) are summarized below:

- There is no properly demarcated boundary for MAP making it difficult to identify and monitor conservation related issues;

- It has a number of heritage structures whose status is not clear. They have a “notified” status as per building byelaws but not as protected structures;

- Many of the structures being tombs and mosques are religious in nature and, therefore, also governed by the Delhi Wakf Board (DWB). The board has also power of notifying; but it has not been checking or has been unable to check new construction. As a result, construction of illegal madrasas without due process being followed and land grabbing/encroachment remain issues of concern. DWB’s proposal for conservation of its heritage buildings has also been languishing for the past six months, as the Delhi government has taken the position that SAD should also be involved in their restoration while, on the ground, DWB and SAD have been contesting court cases over jurisdiction of several monuments;

- There is a lack of tourism linkage. It is not well maintained by the DDA and lacks public facilities, particularly given the large area of MAP – no toilets, no place to sit, to serve light snacks, walks not well maintained, security has been an issue though less so now;

- Vandalism; and most importantly

- Negligible community participation as the local people, involved in their own lives, have yet to show interest in supporting/being a part of conservation efforts. In this, the change in demographics has also become a factor – migrants, especially from the Mewat region of Haryana have settled in the area while residents of Mehrauli have not been using this place as their own (discussions with INTACH Delhi Chapter, The New Indian Express, June 11, 2019).

62. From the above, it is clear that the need for public engagement in the MAP project is essential to be able to actualize its potential as a world class urban heritage park. In pursuance of court’s orders following the INTACH PIL, a number of encroachments in the area on government land have been removed. There have also been suggestions such as why not make them (encroachers) a party to the conservation efforts? To bring lesser known monuments in Delhi under government protection, a MoU was signed between SAD and INTACH in 2008 to protect 92 monuments. Over 50 of these monuments were notified in three phases and 19 more structures were recently notified in the fourth phase. Many of these structures fall in the MAP area or adjacent areas and people have constructed dwellings and sheds inside some of these monuments. For example, a Lodhi-era tomb in Lado Sarai is being used as a fodder store. Initiation of conservation work in such circumstances becomes a difficult task as the local people generally turn hostile (Times of India, conservation shield for 19 monuments, June 5, 2019, https://www.thecitizen.in).

CONCLUSION

63. In a not too long frame of time since the second half of the 19th century to the present, the theoretical framework for conservation of cultural sites/heritage has changed significantly and continues to evolve. This dynamism in the conservation paradigm and the growing willingness to understand and empathize with global cultural diversity, of which there exists today a clearer realization post-Nara, augurs well for the future of conservation. The dominant approach in conservation today, the values-based approach, itself has been adapting, trying to be more inclusive and so has been the charter delineating that approach and most widely referred to – the Burra Charter. It has seen several debates, amendments and expansions. Side-by-side, critiques of the existing frameworks as well as complementary approaches and views flourish. With a growing awareness about the importance of conservation, and new tools of information sharing and participation there is also a pattern of more decentralized conservation visible, especially in the developed world. And this naturally leads to a strengthening of community participation at all levels.

64. The situation is much more complex in a developing country like India where the linkages between conservation and social development need to be clearly emphasized and engraved at the policy level, which could then act as a fountainhead and inspiration for conservation efforts across the country in a decentralized manner and with emphasis on community participation. In a number of instances in India such as in the case of the old city of Shahjahanabad in Delhi, livelihoods get linked to distortions that have crept-in and become entrenched in the prevailing local socio-economic structures resulting in the formation of vested interest groups that oppose or resist conservation efforts seeing these as detrimental to their interests. As a result, litigations slow down forward movement and the traction required for projects to take-off does not materialize. Then, there is also the issue of a visible lack of coordination among the stakeholders, including on the government side, which results in them working at cross purposes. This has been particularly evident in the case of MAP, where the stakeholders (local community, DDA, Wakf Board) do not appear to be on the same page.

65. It is felt that a sustained discussion, as part of a public discourse, on the positive impact of conservation efforts with high levels of community participation and the growing relevance of adaptive re-use where suitable, both on livelihood generation and socio-economic development in general, could eventually lead to policies that formalize these linkages. Thereby, providing a framework and guidelines for community-based conservation initiatives and lead to a better realization of the heritage-linked tourist potential across the country.

Bibliography

Anthem Press (2014). The Ruskin-Morris Connection.

Applebaum B. (2007). Conservation Treatment Methodology.

Barassi S., (Autumn 2007). ‘The Modern Cult of Replicas: A Rieglian Analysis of Values in Replication’, in Tate Papers, no. 8.

Cimadomo G. (2012). Community Participation for Heritage Conservation, p. 94-95.

de la Torre M., Mason R. (2002) Assessing the Values of Heritage Conservation: Research Report, GCI, pp. 3-4.

de la Torre M., MacLean M. G. H., Mason R., Myers D. (2005). Heritage values in Site Management: Four Case Studies, Getty Conservation Institute, p. 5.

Exhibition on Conservation Work at Humayun’s Tomb (2016).

Fielden B. (1987). The Conservation Manual for INTACH.

ICOMOS Charters. INTACH Knowledge Centre Compilation.

INTACH Charter for the Conservation of Unprotected Architectural Heritage and sites in India (2004).

INTACH – Australia Heritage Workshop on Indian Chapter for Conservation held on March 24, 2004.

Argyro L. (2016).Living Ruins, Value Conflicts, pp 108-9.

O’ Connor M., Williams K., Durant J.(2011). A Case-study Analysis of the Values-based approach and the Leventis Project.

National Policy for Conservation of Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains. (2014). Archaeological Survey of India.

O’Connor, M., Williams, K. and Durrant, J. (2013). A Case‐Study Analysis of the Values Based Approach and the Leventis Project. e-conservation Journal, pp.102-114.

Poulios, I. (2010). Moving Beyond a Values-Based Approach to Heritage Conservation. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 12(2), pp.170-185.

Piplani, N., 2018. Theoretical Underpinnings of Conservation Approaches.

Piplani,N., 2018.Introduction to International Charters.

Pye, E. in interview with Hole B. (November 2011).

Ruskin, J. (n.d.). The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Boston: Colonial Press Company.

Sapu S. (2009). Community Participation in Heritage Conservation. The Getty Conservation Institute.

The Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme (2011). Strategies for Urban Regeneration.

The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. (2013).

Tonnies, F. (2002). Community and Society. London: Dover Publications.